February 24, 1917.

The President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, is told a story by the Ambassador to England, Walter Hines Page. The day before, Page had met with British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour and was given a codetext. It was now Pages turned to tell the President about the Zimmerman Telegraph.

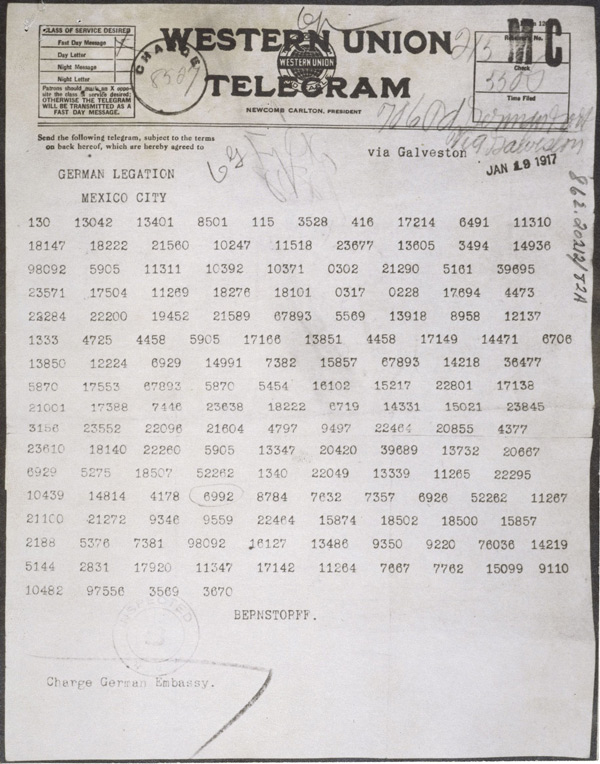

On January 17, 1917, Arthur Zimmerman, who worked in the Foreign Office of the German Empire, sent a message to the German Ambassador to Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. The decoded message was as follows:

“We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain, and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President’s attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.

Signed, ZIMMERMANN”[1]

As early as 1914, Germans had been attempting to entice a war between the United States and Mexico. Although they were sometimes partially successful, the United States did not enter World War I, and Mexico remained neutral. This Zimmerman telegraph was part of an effort to postpone the transportation of supplies and other materials from the United States to the Allied Powers. They had hoped that the Mexican government would declare war on the United States and tie down American forces so that they, and more arms and ammunition, could not be sent to Europe. At this point in time, the German high command believed that they would be able to defeat British and French soldiers on the western front. After doing so, they would then strangle Britain with unrestricted warfare. However, this all depended on no more aid coming from the United States.

After learning of the German’s plan and the Zimmerman telegraph, Wilson was furious. It is said that he felt “much indignation” toward the Germans. Therefore, on March 1, 1917, Wilson published the telegraph so the American people could see it for themselves. Any doubts about the telegraph’s validity would be laid to rest on March 3, when Zimmerman himself held the press conference and told an American journalist, “I cannot deny it. It is true.”[2]

Public opinion towards the war began to change. As early as February 1, Germany had already started using unrestricted submarine warfare against all ships in the Atlantic bearing an American flag. People began to fear for their safety, and rightfully so. Wilson had refused to sign any United States Navy personnel and weaponry to protect merchant ships. But once the telegraph was published, he called for the arming of merchant ships. This would be a movement that would ultimately end when the United States Senate blocked the proposal. However, their opposition would not last long.

On April 6, 1917, Congress voted to declare war on Germany. President Wilson asked Congress for “a war to end all wars.”[3]

[1] “The Zimmermann Telegram,” National Archives, August 15, 2016, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/zimmermann.

[2] Michael C. Meyer, “The Mexican-German Conspiracy of 1915,” The Americas 23, no. 1 (1966): 76–89.

[3] Arthur S. Link, Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917 (New York: Harper & Row, 1972): 252–282.

Leave a Reply